In his One Assembly, Jonathan Leeman observes a biblical pattern wherein local churches assemble together in one place. He also argues that the word ekklesia means assembly, or a gathered people. On these bases, Leeman concludes that the Bible forbids multiple services and sites.

I agree with his observations. When Paul and Barnabas “gathered the church together” in Antioch (Acts 14:27), they brought everyone into one assembly. This is the normal pattern we see in Scripture. A church is a gathered people.

I disagree, however, with Leeman’s further claim that the Bible forbids multiple services because his argument relies too heavily on the Greek word for church (ekklesia) while ignoring other important evidence about what defines a church.

Due to many discussions with pastors and others on this topic, I decided to write this article explaining my friendly disagreement with Leeman. In particular, this article will explain how I understand the word “church,” why Leeman’s position does not persuade, and whether churches can have multiple services.

The One Assembly Argument

In short form, the single assembly argument defines a local church or ekklesia as a single “assembly.” As Leeman puts it: “The cleanest and simplest argument against multi-site churches, I think, is the semantic argument. Ekklesia means assembly, it’s said, and so one assembly is one church.”

By this semantic argument (and others like it), Leeman aims to make an ontological claim regarding the nature of the church (One Assembly, 19). In his own words, “there is no such thing as a multisite or multiservice church based on how the Bible defines a church. They don’t exist. Adding a second site or service, by the standards of Scripture, gives you two churches, not one. Two assemblies, separated by geography or numbers on a clock, give you two churches” (Assembly, 17). The church is thus an assembly in one place, and Leeman sees this as an ontological description of the church.

Leeman also speaks about “the slightly more complex theological question of what constitutes a local church as a church.” Leeman answers that question by saying that “a local church is constituted by a group of Christians gathering together bearing Christ’s own authority to exercise the power of the keys of binding and loosing.” It is worth noting that “the keys” for Leeman include preaching and the sacraments.

Lastly, Leeman does recognize a distinction between “the Church” and “a church” (Assembly, 23). As I will suggest below, however, this recognition plays almost no role in his definition of ekklesia as an assembly.

I have two important clarifications before we continue. First, this is a tertiary issue. Christians can disagree about the question of multiple services without breaking fellowship. Second, I’m not promoting multi-site churches or multiple services. I’m simply arguing that Leeman’s definition of what makes a church is incomplete. So his inference about the ontological nature of the church does not persuade.

My Criticism of Leeman’s Argument

As I trace Leeman’s argument, it goes something like this:

- The word ekklesia means assembly, the gathered people (One Assembly, 18, etc.)

- The word ekklesia can also refer to concepts like the body, and so these are excluded from his study since these senses do not refer to the assembled people (26)

- The word ekklesia regularly appears in the NT to refer to the whole church assembled together (19, 24–25, etc.).

- Therefore, the NT teaches that we should assemble together as one church in one place. We should not have multisite or multiservice churches (16).

One weakness of Leeman’s argument occurs in #2 above because his methodology excludes key places where the Bible defines the church as the body of Christ such as:

- Colossians 1:18 “And he is the head of the body, the church.”

- Colossians 1:24 “his body, which is the church.”

- Ephesians 1:22-23 “And God … appointed him to be head over everything for the church, which is his body.”

- Ephesians 5:23 “Christ is the head of the church, his body.”

Leeman does note that we can speak of the church as the body, but he immediately excludes such passages from his argument and writes: “The single biblical element we’re meditating upon in this book comes from the word itself—ekklēsia in the Greek, ‘church’ in English” (26).

That move in logic I find inscrutable. Paul defines the ekklesia as the body of Christ. So it should be included in the definition of what ekklesia means. Paul also qualifies the meaning of ekklesia, which means that when the church assembles together in one place, it remains the body of Christ. As I will note below, Scripture defines the church with other metaphors too like temple, people, nation, and so on.

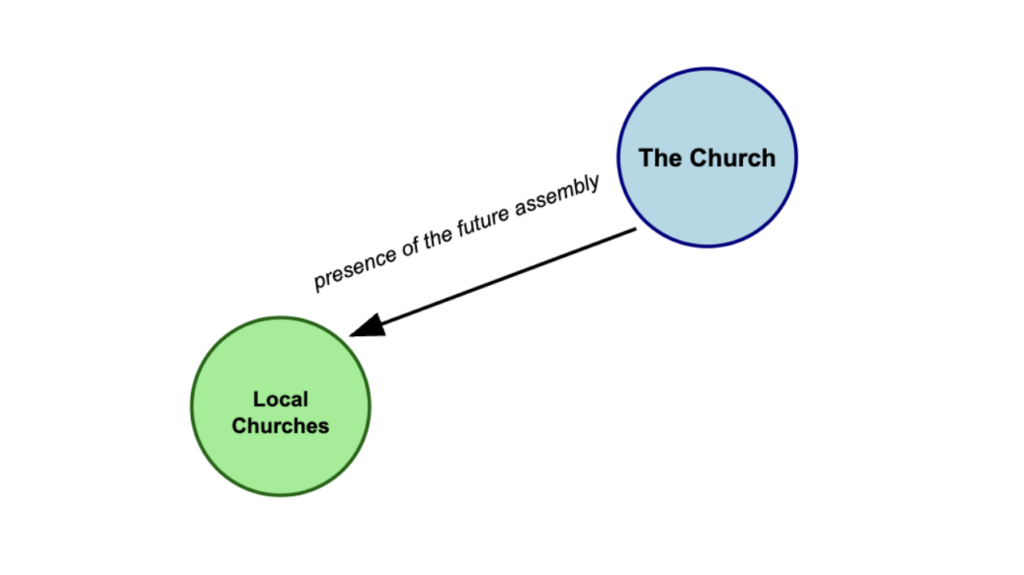

I suspect Leeman excludes Paul’s definition of the church (“his body, which is the church”) because of his non-traditional view of the universal church. When Leeman speaks of the universal church, he calls it a heavenly and future or eschatological church, pointing to Hebrews 12 for evidence of it (79; 128). Notably, he does not cite the traditional and creedal verses on the universal church, such as the ones cited above.

Even though Leeman verbally affirms the reality of “the universal church,” he locates it in the future and does not, as far as I can see, have a logical place for the church as the spiritual body of Christ in his argument. Leeman explains:

“Remember, these assemblies are earthly, in-time outposts of a glorious heavenly and eschatological reality. Indeed, the reason New Testament authors can refer to the scattered church as ‘assembly’ is that its reality is rooted in something even more basic and primary, namely, the future heavenly assembly. We must never read the term ‘assembly’ in the already apart from the not yet. The already entails the not yet. Yet, if the assembly never assembles, how can it be a sign of the not yet? After all, the not yet assembles” (One Assembly, 98).

Leeman thus ties the universal church to the not yet “future heavenly assembly.” While he grants an “already” experience of the universal church, he calls it “a sign of the not yet.” Likely, this ties to his idea that the church is an outpost of the kingdom (41, 63).

Leeman’s view

So when he says, “The gathering manifests the universal church” (23), he does not mean what Christians have traditionally understood by the universal church. He thinks more of the future, eschatological assembly rather than the one, holy, and catholic church united together in faith and the Spirit.

Traditional View

In short form, Leeman does not say the church is the universal body of all those who trust in Christ in this traditional sense. As a consequence, he incorrectly defines local assemblies, which leads him to accuse those who disregard his view as “fighting against Jesus.”

Further, because he misunderstands what the church is, Leeman unpersuasively argues that multiple services ontologically produce multiple churches on the basis of the meaning of ekklesia.

To make my criticism more clear and to show why I find Leeman’s argument insufficient, the rest of this article aims to answer three questions: (1) What is the church, (2) what are churches, and (3) what is a local church? I will conclude that a single service at a church makes good prudential sense but is not required by Scripture’s own definition of ekklesia. Therefore, one can run multiple services but would run into multiple practical challenges in doing so.

What Is the Church?

Scripture speaks of the church as both the assembly of saints who are the body of Christ across space and time and as local expressions of this body in one place and time.

Such definitions of the church also parallel standard Reformed definitions. For example, the Catechism of the Church of Geneva defines the church as “The body and society of believers whom God has predestined to eternal life” (Reid, 102).

The catechism continues by saying “as there is one head of all the faithful, so all ought to unite in one body, so that there may be one Church spread throughout the whole earth, and not a number of Churches (Eph. 4:3; 1 Cor. 12:12, 27)” (Reid, 103).

Herman Bavinck similarly writes, “The community of those who share in Christ and his benefits is called the church'” (RD 4:275). After all, the church is the body of Christ, and there is only “one body and one Spirit” (Eph 4:4). In Bavinck’s language, “it embraces all believers on earth at all times and places” (RD 4:282).

Importantly, the Second London Baptist (1689) first defines the church catholic (§1) before it speaks of particular churches (§7). This dual idiom that defines the one church in its general and particular character matters. Importantly, there is one definition of the church that applies to the church in its universality or locality.

Given the Bible’s identification of the church with the body of Christ, Paul can say: “There is one body and one Spirit—just as you were called to the one hope that belongs to your call—one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of all” (Eph 4:4–6). If there is one body, there is one church because the church is the body of Christ. Thus, Calvin says, “there could not be two or three chuches unless Christ be torn asunder” (Inst. 4.1.2).

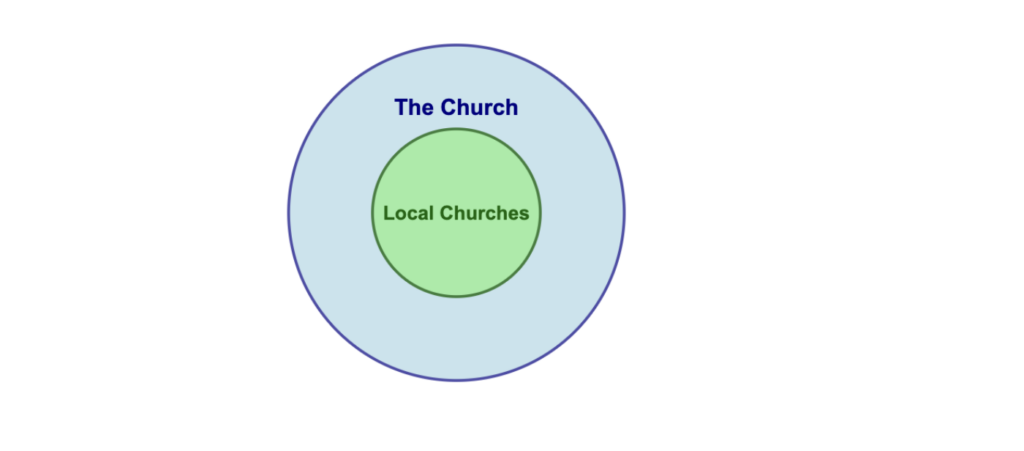

But this one body, the church of Christ, does not mean that it cannot have local expressions of that body in Corinth (1 Cor 1:2), nor does it mean that it cannot have members of that one body in one local assembly (1 Cor 12:27). Calvin again can speak of us being “members” of the “church” (Inst. 4.1.3), and he can speak of “individual churches” under “the church universal” (Inst. 4.1.9). Calvin, like Paul, can speak of the church as one body which gathers together in various places.

Leeman mostly agrees with this premise but methodologically excludes passages in the Bible that define the church as the body of Christ, such as Ephesians 5:23: “Christ is the head of the church, his body” (also Col 1:18, 24; Eph 1:22–23). So his definition of the gathered assembly is incomplete.

What I am getting at is that Scripture defines the ekklesia in ways that allow for the word to describe the entire assembly of the saints (the universal body of Christ) and a particular assembly of that body of Christ (the local church). There is one definition of the one ekklesia, which can be distinguished in both its universal and local scope. And this distinction matters when we define local assemblies.

Paul speaks of, “his body, which is the church” (Col 1:24). Leeman puts such passages to the side and highlights a local definition of the church based on the lexical sense of ekklesia. But that cuts off the explanatory power of how each assembly is an expression of the “one body” because of the “one Spirit” (Eph 4:4).

Other Metaphors for the Church

Other metaphors in the Bible also help to show this double idiom of the church as the universal body of Christ and the church in a single place as a local instance of the whole. For example, Paul calls the church a temple with Christ as our cornerstone in Ephesians 2, which parallels his arguments in 1 Corinthians. It also parallels the body and head language because we are the stones of the temple with Christ as the cornerstone.

Peter speaks of the church as a “spiritual house” and a “holy priesthood” (1 Pet 2:5). Like Paul, he calls us “living stones” of the cornerstone (1 Pet 2:5, 6). Peter even adds that the church is a holy people: “you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for his own possession” (1 Pet 2:9). Such language reminds us, to borrow a phrase from Oliver O’Donovan, that we are a veiled political society as the church.

The Nicene Creed and Christian theologians have affirmed such a definition by confessing the “one holy catholic and apostolic church.”

I could list many more witnesses, but I only want to illustrate that when the Bible and the reformers speak about the universal church, it is not a future reality as Leeman claims but a parallel reality. Local assemblies subsist as a local expression of the body of Christ. Imagine a Venn diagram that contains the Church. Within it, various circles of local churches would exist. But they are both the church, the body of Christ, the temple, the people, a holy nation, and a commonwealth.

So our definition of ekklesia should include all believers united to Christ by faith, which is how Paul and Peter speak of the church. They qualify the lexical sense of ekklesia by showing what kind of assembly the church is.

It turns out that the assembly (or church) is the body of Christ, the temple of God, living stones, and more besides. And it includes in that assembly all of those united to Christ by faith. And yet the Bible regularly speaks of “the church of God that is in Corinth” (1 Cor 1:2) and “the churches of the Gentiles” (Rom 16:4). How can we put these pieces together?

What Are Churches?

The church in Corinth or the churches of the Gentiles refer to local expressions of the body of Christ in one place. In such places, the word ekklesia refers to an assembly in one local place that represents the body of Christ in that location. On this narrow point, I have no problem with Leeman’s semantic argument.

However, given that Paul can and does define ekklesia as the body of Christ or the Spiritual temple of God (along with Peter), Leeman’s semantic argument needs revision. Even Jesus, when he says “I will build my church” (Matt 16:18), clearly had in mind his spiritual body—those united to Christ by the Spirit he would give on Pentecost.

So the question we need to ask is not just what ekklesia means lexically, but also how the Bible defines and qualifies the ekklesia of Christ, who is our head. Once we do that, we can begin to piece together the local definition of church, which flows downstream of its wider definition.

The church of Corinth, the churches of the Gentiles, and other like terms, by definition, must refer to the body of Christ in one or more geographical locations. Hence, we call them local churches. Yet since there is “one body and one Spirit” (Eph 4:4), we know that theologically there is one church, one body, which we are in Christ, who is our head.

When a local assembly runs multiple services or has multiple sites, prudentially, I find this less than ideal. I agree with Leeman here. Yet I do not think I can say that the word ekklesia and its use in the New Testament require me to say that.

Instead, Scripture points me to the body of Christ, the temple of God, as the most general definition of the church. It directs me then to speak of local expressions of “the church, the body of Christ.” It tells me to speak of the Church of God in Stoney Creek called Redeemer Church, or something along those lines.

Pointedly, these distinguishable idioms of speaking about the church always refer to one reality: all those united to Christ by faith through the Holy Spirit. The local assembly specifies a subset of the church in one place, organized as I will note below, by key marks of the church: word, sacraments, and discipline.

John Calvin’s Geneva

John Calvin’s Geneva is instructive. In a 1546 document on visiting “The Country Churches” (the local expressions of the church), Calvin also speaks of “the whole body of the Church of Geneva” which included many parishes, pastors, and service times. The same document also speaks of The Church (the whole body of Christ).

Calvin weaves between universal and local idioms readily. This is normal in theological literature across the centuries because of the organizing concept of the church as the body of Christ, universal and localized.

Interestingly, the Church of Geneva contained many parishes, pastors, and services, and yet Calvin could simply call this collection the Church of Geneva. We might say they had a multisite and multiservice organization. But this was normal for his place and time.

A reason why Calvin found this arrangement pastorally useful is that he defined the church as “The body and society of believers whom God has predestined to eternal life” (Catechism).

In light of this biblical definition of the church, Calvin’s idiom parallels how the Bible itself can speak of the church as the whole body of Christ, how it can speak of the church of Corinth (1 Cor 1:2), and how it speaks of the churches of the Gentiles (Rom 16:4). Scripture provides expansive language for how to speak about the church or churches, because Scripture sees the Church as all those united to Christ in the Holy Spirit. We can thus have much freedom pastorally when we use the word church.

Leeman, by contrast, focuses his attention on the historical or lexical sense of ekklesia and methodologically mostly excludes the language of the body of Christ in his discussion of the gathered people (Assembly, 26). I believe this decision weakens his ability to understand the ontological status of the ekklesia. And it leads him to inferences about multi-site churches fighting Jesus: “We fight Jesus by redefining the church.”

What Is a Local Church?

If I stopped writing here, I might give the impression that the visible form of the church is unimportant. I mean nothing of the sort. I deny that an online-only church can administer the sacraments since they require physical water and physical wine and bread.

When Christians come together in one place, the Bible teaches us to organize ourselves around the Word, sacraments, and discipline (the keys). The Bible also teaches us to appoint elders and deacons. It has a substructure for congregational life that we must adhere to. I agree with Leeman (or he with me) on these points.

But a local church is not the local church. A local church is a local assembly of the body of Christ in a specific place, marked by a ministry of word, sacrament, and keys. Such a congregation represents a local church, a local assembly of the one body of the one Lord Jesus Christ due to the one Holy Spirit that proceeds from the one God and Father of all (cf. Eph 4:4–6).

This leads to a key point: One Assembly provides prudential arguments for a single assembly, but not a complete biblical argument. Leeman uses phrases like “those who redefine the church fight Jesus.” To do so with an argument that excludes a key biblical definition of the church (body of Christ) and with a semantic argument that feels suspiciously like the word-concept fallacy, Leeman overstates his case and evinces a partial misunderstanding of what the church is.

One of the best examples of Leeman’s incomplete understanding of the church is his second appendix in which he tries to make Acts 9:31 not refer to “the church throughout all Judea and Galilee and Samaria” but rather to “the churches” (plural) due to the use of the Greek preposition kata and a textual variant (128).

While his arguments have some merit, the simplest solution is to note, like the rest of Scripture, that the ekklesia is the body of Christ that comprises the whole society of believers. So we can speak of “the church throughout all Judea and Galilee and Samaria” and we can speak of the church of Judea, the church of Galilee and the church of Samaria.

Had Leeman embraced a traditional definition of the church, such as in the Nicene Creed, he would not need to make such a division between the future or universal assembly and the local assembly that by sign evinces the presence of the future in that assembly.

For my part, I say that the church is one because the body is one. All those united to Christ are the church, whether local or universal. It is the same definition. So I am free to read passages like Acts 9:31 without issue.

Conclusion

As I conclude, I want to point out how Leeman defines his own argument in summary form: “Multisite and multiservice churches repudiate the Bible’s definition of a church, redefine what a church is, and so reshape the church morally. And all that means these models pick a fight with Jesus” (35).

But Leeman himself under-defines what a church is and finds himself unable (or unwilling) to let the Bible’s own idiom shape his ecclesiological language. In so far as he speaks about the people assembled as the ekklesia, we agree. But unless he says more—as much as the Bible does in fact—his view of the church remains incomplete.

The Bible qualifies and defines the ekklesia with various metaphors (body, family, temple, etc.). These internal definitions and qualifications need to shape our understanding of a local assembly. Leeman does not model that in his book. Instead, Leeman privileges an important idiom of ekklesia and fails to persuade that this means churches must only have one service.

Oddly enough, I find myself nodding along to his pastoral wisdom and seeing the prudential fittingness of a single assembly for church order. Weirdly then, I am both an ally and a critic of Leeman’s approach. I suspect there are many others like me.