I love teaching women how to study the Bible. Giving them the tools to unearth the treasures of God’s Word for themselves brings such great joy. As the women’s ministry director for SOLA (The Gospel Coalition Quebec), I have the privilege of doing just that.

All believers can and should learn to interpret the Scriptures for themselves. We should do so in community, leaning on the collective wisdom of our spiritual leaders, the family of God at our local church, the saints throughout church history, and brothers and sisters across the globe.

Yet we shouldn’t rely exclusively on others to teach us the Word of God. The job of pastors is to protect their flocks from false teachers and to equip them for the work of the ministry. God has endowed each of us with the Holy Spirit to guide us in all truth (Jn 16:13).

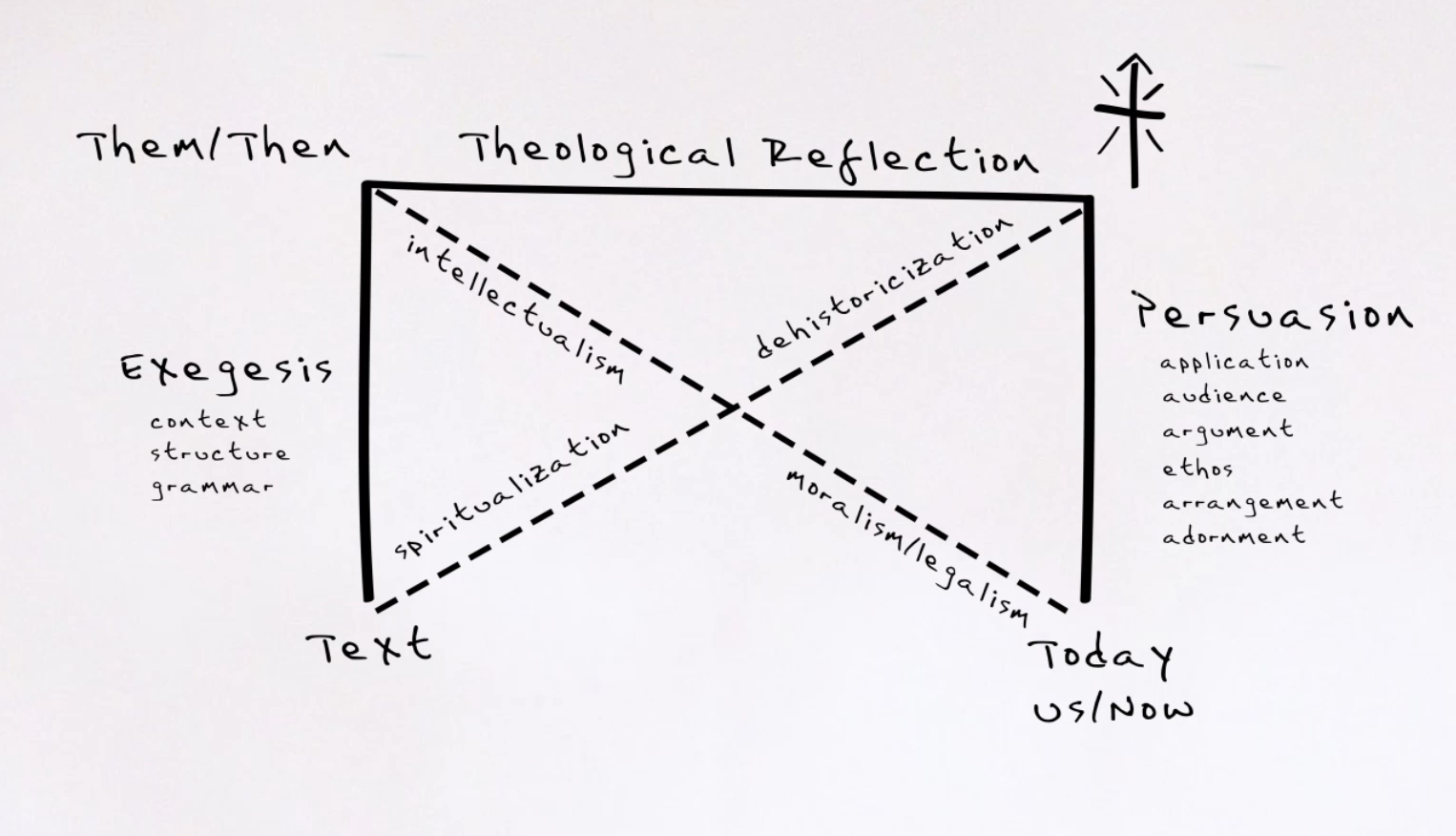

Thankfully, the process is far more straightforward than one might think. We just need to follow a simple pathway from the ancient text (them/then) to the 21st century (us/now).1

Identify the Structure

Begin on the bottom left-hand side of this graphic with your chosen text. Imagine you want to know how to interpret Exodus 1. The first step of interpretation we need to take is to identify the structure of our passage. And that is because every text has a structure. This structure reveals an emphasis. The emphasis must shape our message. The best method to determine the structure of a text will depend on its text type.

Poetry

A Psalm, for example, is divided into stanzas, which we can identify by noticing the use of repetition, contrast, and changes in tense, tone, speaker, and person/people being addressed.

Discourse

Found most commonly in the epistles, determining the structure in this text type will require that we brush up on elementary school grammar and consider conjunctions (connecting words or phrases like therefore, so that, and, but, because), prepositions (words that indicate the relationships between elements in a sentence such as over, under, before, after, in, out), repetition, and changes in time or subject.

Narrative

Large portions of the Old Testament, as well as the Gospels, consist of narrative. We can identify their structure as we consider how each scene involves changes in its main characters, time or location, and themes. Sometimes, understanding the plot arc of the story will also help (exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution). In Exodus 1, I identified 4 distinct scenes.

Four Scenes in Exodus 1

Family History (v. 1-7)

Forced Labour (v. 8-14)

Fast Labour (v. 15-21)

Furious Pharaoh (v. 22)

Understand the Context

Your next step to properly interpret a passage will be to seek to understand its literary, historical, and biblical contexts.

Literary Context

How do the literary units immediately before and after ours inform the meaning of our text? In the case of Exodus 1, the most significant element of its literary context is the closing chapter of Genesis. This book of beginnings ends with Joseph dead in an Egyptian coffin. And before breathing his last, he asks his brothers to promise to take his remains with them to the land God swore to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (Gn 50:24-25). Joseph dies with the promises of God on his lips. The importance of this reality will become evident as you study the text.

Historical Context

To evaluate the influence of the historical context, we need to think of two distinct sets of people: The actors in the drama unfolding in our passage and the original recipients of the book in its completed form. So, for Exodus, the characters of the story in Exodus 1 consist of the king of Egypt (v. 8), the people of Egypt he enlists in his sinister plan (v. 9, 22), the multiplying Hebrews suffering under the boot of oppression (v. 12), and Shiphrah and Puah, the Hebrew midwives who fear God more than Pharaoh (v. 21).

The second group of people to consider is the original audience of the book of Exodus. Moses recorded the events we read in Exodus 1-40 at the beginning of the wilderness wanderings. So, the recipients of the book consist of the first generation of Hebrews who experienced the deliverance of God from slavery in Egypt.

Having identified these two groups, we need to next put ourselves in their shoes. We need to try to understand what they were going through. This begins with us praying and asking the Spirit to help us imagine what the various parties were experiencing in the unfolding drama. What was life like for the Hebrews as foreigners in a land in which the king incited his people to turn against them? What were the midwives feeling when Pharaoh ordered them to commit infanticide? This can only take us so far, of course. That is why a good Bible dictionary can inform us about the geography, topography, and cultural practices of the time.

Biblical Context

The biblical context refers to the previous Scriptures that the author cites or evokes to make his argument. In the case of Exodus 1, we hear echoes of the Cultural Mandate (Gn 1:28) and the Abrahamic Covenant (Gn 12:1-3). Moses borrows from the vocabulary of both these key passages in his first book, and this reality will influence how we interpret our text.

Discovering the Gospel Connection

Once we have determined the context and structure of a passage, we should be able to grasp its meaning for its original audience. This is an essential step in biblical interpretation because if we jump straight from our text to the gospel, we risk spiritualizing the text and ignoring the author’s purpose for writing. After all, the book of the Bible we are studying was written for a particular group of people in a specific geographic location, and we do a disservice to the Scriptures when we ignore that and make it immediately about us today.

Similarly, if we move straight from them/then to us/now without connecting our text to the gospel, we are in danger of moralizing the text. By this I mean giving the moral imperatives of the passage without the grace-filled power to carry them out as new covenant believers.

Therefore, for believers in Jesus Christ, the next step along the pathway of interpretation is essential. Since all of Scripture points us to Christ (Lk 24:27, 44-46), we must establish how our passage leads us to the cross and resurrection of Jesus. How does Exodus 1 give us a signpost to the gospel? By showing us that the Abrahamic covenant was partially fulfilled in the numerical growth of the patriarch’s physical descendants. But its ultimate fulfillment will come as God redeems a countless multitude from every nation, tribe, and tongue.

Final Stop: Us/Now

Once we’ve connected our text to the gospel of Jesus Christ, we can finally arrive at our final destination: Us/Now. Can I summarize the message of my text in one simple phrase? Once I have, can I apply this ancient story to the 21st century? I summarized the message of Exodus 1 as follows:

The God of the impossible keeps his promises, so fear him and not the powers of this world.

I drew the following points of application from Exodus 1:

- God chooses to use insignificant people (in the world’s eyes) who fear him (like two Hebrew midwives), so let us fear God and trust him to use us, too, for his glory.

- God was faithful to keep his promises to Abraham, and he continues to keep his promises to us today. Trust him to do the same for you.

Conclusion

I said at the beginning of this article that the process is simple. I didn’t, however, say that it was easy. It takes hard work and perseverance. It requires setting aside time and energy for study and reflection. It may also necessitate setting aside funds for a few solid resources like a Bible dictionary and/or commentary. The return on your investment, however, promises to yield eternal dividends. For with each passage you study in this way, you will be unearthing precious gems hidden deep in the soil of God’s Word. What better way to invest in eternity?

1 I’m indebted to The Charles Simeon Trust for this teaching tool. In their workshops and courses, they refer to this as “The Pathway of Preparation,” as their audience is pastors and Bible teachers. I have chosen to refer to it as the pathway of interpretation in the context of this article because my purpose is to apply these principles to all believers and not only those who teach in formal settings.